In Defense of Single Women

If, like me, you’re a millennial between your mid-twenties and mid-thirties, it might feel like everyone is pairing off. And while your rational, independent, feminist core knows that the timeline to couple up and settle down is simply a societal construction rooted in outdated patriarchal standards, maybe a part of you feels like you are doing something wrong. Today’s social media overshare certainly perpetuates these worries. Amongst my urban millennial cohort in America, engagements are being announced in what seems like a domino effect. The American half of my Facebook feed wants to plant a time bomb in the back of my head for an idea I don’t actually agree with. (Or maybe it’s simply turning 28, where I can say I’m officially ‘approaching thirty’).

Speaking of thirty, nowhere is the stigma against single women more pronounced than in China. In a country where 90% of women marry before thirty, a woman who is still unmarried at thirty is considered “left over”.[1] And can we take a minute to talk about how awful this term is? As if a single woman becomes, after a certain point, the last kid picked for the kickball team, or the remaining pile of lemon Starbursts.

Of course, the definition of an “acceptable” window* to stay single before marriage varies from country to country. I live in France, where I know very few people my age who are actually married or engaged. Is it just my social circle, I wondered, or are the French less apt to share their engagement photos? Or wait — maybe they simply aren’t doing marriage with the same frequency, or at the same age, as my American counterparts. In 2017, the average age of marriage for a woman in France was 36[2]. In America, it was 27[3]. Here, it’s far more common for couples to enter a civil union based on cohabitation than jump straight into marriage. This doesn’t mean, however, that being single doesn’t feel like an anomaly. When I’ve been single in this country — about half of the past five years — I occasionally felt like something was wrong with me. Often this was the result of backhanded compliments — “But you’re so smart / cool / pretty / (insert nice adjective)… How are you single!?” — as if it weren’t, in part, something I wanted to be or a label I wasn’t actively choosing to live.

tristan-colangelo-221273-unsplash.jpg

Let’s not forget, on the eve of our favorite** Hallmark holiday, that the empowered single woman is and has always been a force to be reckoned with, and she is not, contrary to what we might believe, a recent apparition. I recently finished Kate Bolick’s Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own, a lovely read from start to finish that I highly recommend. It’s a personal memoir of unmarried adulthood intertwined with a spotlight on five famous women of yore who refused to yield to the marriage plot: columnist Neith Boyce, essayist Maeve Brennan, sociologist and writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman, poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, and novelist Edith Wharton.

Even in 1900, when the average age of marriage was 22 for women, many adult women were choosing not to get married. Although modern capitalism has its flaws, the opening of the capitalist workforce to women following the Industrial Revolution allowed a certain form of independence previously unknown to them. Before 1900, even unmarried women were dependent, in some way or form, on men. Nuns were under the watch and care of male priests, sex workers on men to “protect” them, unmarried women on the money and material support of male family members with jobs. But in the wake of the new educational and social developments of the era, more women went off to work and were determined to build independent lives for themselves and carve out a place for themselves in spaces where males have previously dominated.

This middle-class New Woman who sought new opportunities and freedom, living alone and supporting herself, was originally called a bachelor girl, a term coined in 1895. Interestingly enough, the term bachelor is now exclusively reserved for men, bringing up an image of a single male whose connotation is mostly positive: an “eligible bachelor,” a “bachelor pad.” His modern female counterpart, the bachelorette, brings to mind either a young single woman who is desperate to find the perfect match at any price (as we know from the TV show of the same name), or a woman on one last hurrah with her female friends before getting hitched. I find it funny that the French call bachelorette or bachelor parties, respectively, “enterrements de vie de jeune fille / garçon.” This literally means the “burial of the young boy’s life / young girl’s life,” as if that youthful part of you is about to be dead once married.

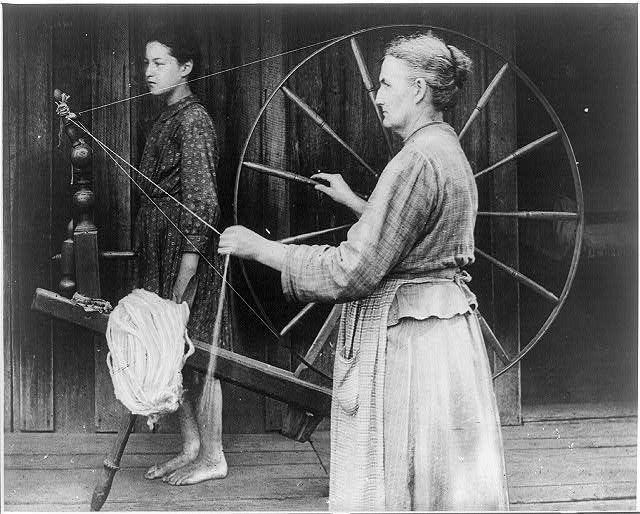

The spinster is simply an older version of a bachelorette, an unmarried woman past a certain age who should no longer hold out hope for romance. Although this term was initially a way to designate an independent woman who worked spinning wool, it quickly became pejorative. (This only makes sense, because the patriarchy fears an independent woman who works and for whom a man serves no practical purpose.) Absurdly enough, it was only in 2005 when England and Wales stopped using these terms on official government documents.[4]

spinster LOC.jpg

Reading Bolick’s book has allowed me to take a step back and analyze my own relationship habits and values and what I hope for myself. I’ve never identified with serial monogamists — those people that jump from relationship to relationship, not taking the time to step back and re-center for themselves. My past two relationships had some deep elements of codependency to the point that after both crumbled, I spent at least a year single, and when I did, it felt like breathing again. I needed that time to be able to move on and actually open myself up to someone new.

Now that I’m happily seeing someone, I’m reminding myself to embrace the singularity of each person within the relationship. When I meet a new person I’m interested in, I’m now able to ask myself: Do I like and respect this person for who they are, unrelated to me? Or am I merely liking the projected idea of us together? Amanda de Cadenet puts it well in her memoir It’s Messy: “I’m not really down with the old-school notion of marriage, where ‘two people become one’. I’ve never understood the concept of two half people coming together to make a whole person.…The ‘romantic’ idea that you must deconstruct your own boundaries in order to merge with someone else is codependency at its most extreme.” A healthy relationship, for me, is that middle part of a Venn diagram, a peaceful overlap of two individuals who still retain the defining elements of their singularity.

When I read Kate Bolick’s plea for us to reclaim the term spinster is that in us “which is independent and self-sufficient, whether you’re single or coupled,” I felt a sense of relief. I can still book an impromptu trip for me and myself only. I can be loud or clumsy or awkward, because that’s who I am, and I’m past the point of apologizing for it. And of course, if we’re in relationships, we owe our partners this same acceptance that we expect to receive from them.

So whether you are single or seeing someone this Valentine’s Day, why not make a resolution to nurture your individuality with as much care and attention as you would give your partner?

* Just kidding, of COURSE there should be no dictated window.

** Please smell my sarcasm!

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/may/12/china-leftover-women-property-boom

[2] https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/1892240?sommaire=1912926

[3] https://www.womenshealthmag.com/relationships/a19567270/average-age-of-marriage/

[4] https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/where-did-spinster-and-bachelor-come-180964879/